Director at LumenLab, Singapore

The concept of a “sandbox” is widely used in the technology world. A software program goes through multiple iterations, sometimes in the same month. Before a new iteration is deployed to customers, it needs to be tested in a way that does not affect real customers, but has access to every other aspect of a real world environment. In theory, that is referred to as a sandbox.

At the beginning of this decade, financial regulators were faced with an onslaught of new technologies, startups and capital funding them. It did not take the regulators long to implement a solution with a bit of regulatory spin on it for this technological flood.

Two years ago the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in the UK launched the first formal global regulatory sandbox. The overarching concept is simple — a controlled environment for any business organization to test and prove its new business before getting final approval from the respective financial regulators/authorities.

Every new business has multiple risks in the financial world. Will the new technology work? Is the customer’s personal data secure? Is the system secure from hackers? These are but a few examples.

FCA’s concept of a regulatory sandbox lets new businesses experiment with new technologies, it allows regulators to test and understand these new technologies and finally—and perhaps most importantly—it does not burden new businesses with overbearing regulations before the actual launch.

There are a few technologies in fintech that haven’t launched but are being tested around the world—these include using bitcoin as a remittance channel, using electronic health records for life insurance underwriting and a financial robo-adviser/wallet that has a holistic view of an individual’s finances.

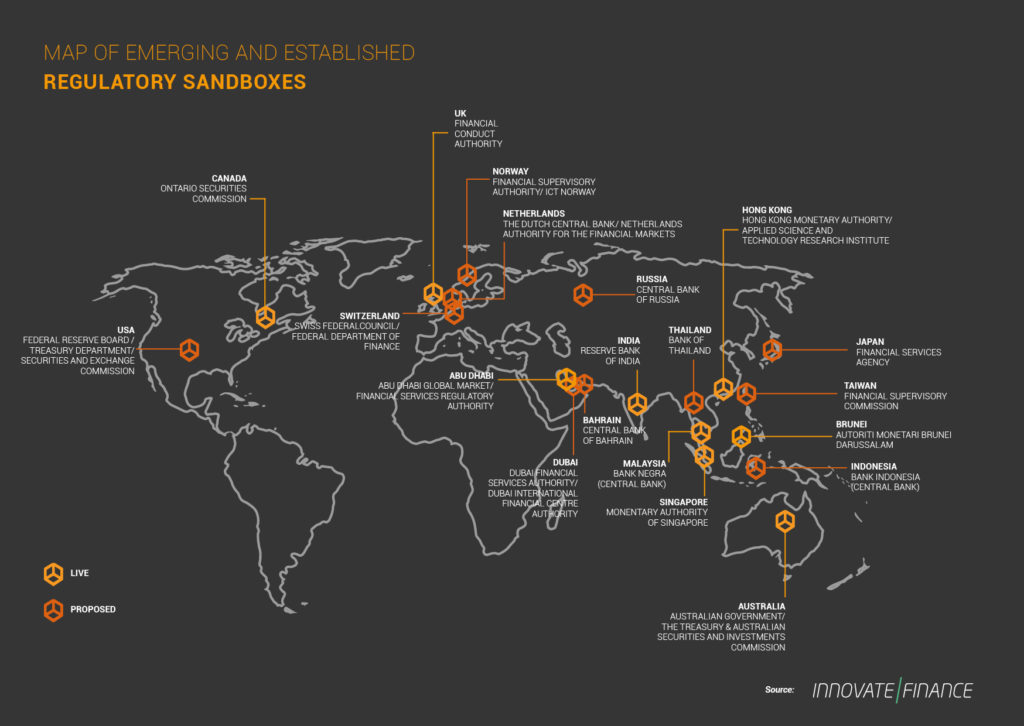

The map shows a view of all the regulatory sandboxes that are live or being planned around the world. The UK is a great example of what has worked in a regulatory sandbox—clear guidelines, yearly cohorts and transparency of applicants.

What About Asia?

Things are altogether different in Asia’s developing economies. First, in these countries, the infrastructure is developing. Apart from India, the concept of digital identity is only evolving in countries such as the Philippines and Indonesia.

Moreover, in these countries, bureaucracy is generally a bottleneck since multiple government agencies work in silos with differing incentives.

For example, regulators handling hospitals and insurance companies are separate. However, any effort to use health records for insurance underwriting needs new regulations, which means these two different regulators need to work together, but there are no incentives for them to do so.

Customers in developing economies are completely different from those in developed economies, especially in terms of income levels. In simple terms, people moving from just above the poverty level to low-middle-income status—the biggest growing consumer section in emerging Asia—only have so much disposable income, and so they need tailor-made products and services.

Design thinking warrants that any new business should start from the customer. Regulators are faced with the conundrum of choosing between the benefits of allowing new untested technologies from developed countries into emerging Asian markets, or being labeled “risk averse” if they deny any such experiments.

Emerging Asian economies have eagerly jumped onto the concept of the regulatory sandbox. Regulators in Asia realized that a regulatory sandbox in the hands of a dedicated team within the regulatory body is a silver bullet. And as a result, today Asia is home to a large number of them.

However, most Asian regulators have yet to recreate the success of the FCA. In addition to the good features—for example, transparency—adopted from different developed countries’ sandboxes, below are a few more recommendations to streamline the development of sandboxes in developing Asian economies.

Prioritize Focus Areas

Developing Asian countries need to prioritize different issues depending on their economies. Targeted releasing of different areas for sandbox applications can streamline fintech innovations that benefit the end consumer in these countries.

For example, remittances are of utmost importance in the Philippines and Bangladesh. Regulators in these countries should focus on fostering innovation, while controlling risks, to weed out illegal remittances and ensure that the end consumer gets the most effective exchange rate.

Even a one percent difference in the exchange rate for remittances can make a significant difference to the family being supported back home, and that is one of the key reasons that explains the prevalence of illegal channels for cross-border fund transfers. Australia, although not an emerging economy, started its sandbox by targeting the securities market and is now moving into other areas.

Provide Regulatory Leeway

Regulatory burdens make it hard for new businesses to innovate. Regulators in emerging Asia need to create special rules within the sandboxes they set up for new businesses to showcase their business models, assure regulators that risks are controlled, and thereby attract capital to build well-proven models.

For example, robo-advisers are a great way to enable the burgeoning middle class to put their savings into equities with a view toward investing and long-term retirement preparation; Thailand has none of those at the moment.

There are international brokerages such as interactive brokers that enable robo-advisers to operate in other parts of the world and are licensed in Thailand. However, there are no traditional Thai banks/ brokerages that provide these new services to their consumers. Regulators could ensure that these new businesses are allowed to partner with banks, educating consumers on how to save a little every month toward their retirement without expectations for short-term returns.

Elsewhere in Asia, Indonesia is a great example of where the regulators have worked with new businesses to create regulations around peer-to-peer (P2P) lending.

Provide Test Beds

Regulators need to be proactive to provide test beds for more disruptive innovation.

For example, insurance penetration is significantly low in most emerging markets when compared to developed economies. No country to date has enabled real-time health insurance underwriting or death claims payouts in life insurance. With the benefit of a clean slate, countries such as Malaysia could take steps that would benefit consumers significantly. Malaysia has a system of death certificates.

If they could centralize all death certificates and allow life insurance companies access to them, then life insurance payouts could become instantaneous—thereby providing customers with cash in times of dire need. China is creating different systems with centralized health records and will hopefully take the lead in marrying healthtech and insurtech.

Think Out of the Box

Sandboxes are a great concept, particularly in developing economies that still don’t have the necessary ecosystems required to support and promote innovation. In their role as catalysts, they are here to stay, but it will be important for regulators to empower the teams responsible for them, so that their benefits can be realized to the fullest.

Regulators also need to provide the teams with the ability to come up with streamlined plans. Instead of asking a new business to mention the rules/regulations that it would like to be relaxed, it would be helpful to have a checklist of sorts before the new business applies for the sandbox.

They should also have the ability to affect/incentivize other government agencies to bring together the power of many rather than that of just one. That is also important to ensure that initiatives are not pulled in different directions.